A Compendium of Sail Information

The most interesting thing to me about the Age of Sail is the textiles used to make the sails. But as I have tried to find out more about them, I have been surprised at the dearth of published knowledge, especially compared to the huge amounts of information easily found about the wooden and metal parts of the ships. Finally I have found some good resources to provide answers to many of my questions. (To make this information flow a little more smoothly, I am going to put all these sources at the end of the post.)

Question 1: Why do we call sailcloth “duck?”

Answer: The Dutch word for sailcloth is “zeildoek.” Doek is Dutch for cloth (generically) and zeil becomes sail in English…Holland was a major supplier of sailcloth and raw materials, trading in flax and hemp for hundreds of years. Eventually, the word “duck” became associated with a heavy fabric and was applied to cotton canvas when it was first manufactured in the United States.

Q 2: So are sails mostly made from linen, or cotton? Or both?

A: The most popular fabric for sails from the earliest times through the mid-nineteenth century was finely woven linen made from flax, but a more coarsely woven fabric made from hemp was also widely used.

During the Age of Sail, duck was the equivalent of today’s gasoline and diesel fuel as a strategic war materiel….The opening of the American Revolution put an end to the plentiful supply of duck through the usual British sources, however Holland and Russia duck was aggressively smuggled into the colonies through clandestine channels…

…[C]otton sail duck production in the United States began prior to the War of 1812….[T]he supply of imported duck was cut off (just as it had been during the Revolution) but domestically grown sea island (off the Georgia coast) cotton now enabled a supply of sailcloth to be maintained. The price of duck went down with the introduction of the power loom during the 1820s and by 1831 it was selling at thirty-five cents per yard. By mid-century, millions of yards of duck were being produced, largely in Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Baltimore, Maryland.

Q 3: If only I could see an old-time movie that showed me the process!

A: This one was made about 100 years later than the period we are talking about, but it gives you the gist in a minute and a half!

Q 4: So is one fiber better than the other?

A: The change-over from flax to cotton sail duck in the navy proceeded slowly, as more conservative elements did not trust the newer fabric to perform as well the traditional flax canvas with its centuries of proven dependability and predictable characteristics. The U. S. Navy conducted tests and the results were inconclusive as to which material was better. Both materials had qualities better suited to specific purposes, and were frequently used in conjunction with one another, both in the navy and commercially.

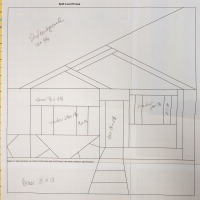

Q 5: Of course a full sail was too big to be woven in one piece. What size pieces of cloth were used, and how were the sails put together?

A: Standards for British manufactured sailcloth were enacted in 1746. In addition to requiring British sail makers to mark each new sail with his name and address, the size of a bolt of sailcloth was standardized at twenty-four inches wide by thirty-eight yards long. Sails were stitched up from multiple strips of sailcloth, and edged with hemp bolt-ropes to keep their shape and distribute stress along the extremities of the sail, and provide anchor-points for rigging components.

By Helge Klaus Rieder (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

This diagram shows the many widths of sailcloth used, and where they were reinforced. Georges Clerc-Rampal [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

A: Of course it would vary with the ship, but the USS Constitution‘s largest sail was 3,366 square feet. Her smallest was 337 square feet.

Reaction: That one large sail has more than twice the square footage of my house!

A: (continued) The total square feet of all Constitution‘s sails is 42,710. An acre is 43,560 square feet.

Sail plan for the USS Constitution, from Wikimedia Commons.

July 2, 1997. The USS Constitution sails independently for the first time in 116 years. By Journalist 2nd Class Todd Stevens [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

A: Sails would have been contracted out to a local sailmaker.

Q 8: Can you give me an example of the numbers of sailmakers working?

A: In 1836, twenty-seven sailmakers worked in New Bedford [Massachusetts] at six different sail lofts, and by 1859 their numbers had nearly tripled.

Zuiderzee Museum,By Helge Klaus Rieder (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

A: A common practice in nineteenth-century shipping was for sailmakers to accept shares in a vessel in lieu of cash, which not only could bring in a good return on their investment, but would also lock in that vessel’s sailmaking work.

Q 10: Besides powering the ship, what other uses did sails have?

Here in the doldrum calms the sailing ship spread her old, patched, and weakened sails, There was no reason to allow good sails to flap themselves to pieces or to hang down for weeks as flat as boards soaked with the weight of continual rains…

Sails would be stretched across the deck to catch rain water with which to replenish the ship’s supply. Some vessels invariably sailed without sufficient fresh water to last a passage through. The masters of these ships depended upon the doldrum rains to fill the water takes…

Considerable care had to be exercised in storing this rain water caught in sails and bailed out in buckets. It was never mixed with the water already in the tanks, but was poured in those already emptied and kept separate. For some reason, not clearly understood, it was never safe to mix rain water with the regular ship’s supply. If this was done all the water in the tanks might turn black and become so tainted as to be unfit for use.

Q 11: Are there any craftspeople still doing this work today?

A: Yes, there are a few. Nathaniel S. Wilson in East Boothbay, Maine, is one, and Carol Hasse of Port Townsend, Washington is another.

Sources:

For Questions 1, 2, 4, 5: “The Great Age of Duck“, by John Frayler, from the National Park Service publication of Salem Maritime National Historic Site, Pickled Fish and Salted Provisions, Vol. VII, number 4, Sept. 2005.

For Question 6: from All Hands on Deck, a lesson plan book produced by the USS Constitution Museum. I bought my copy at a thrift store for 75 cents, but now it is all available online!

For Questions 7,8,9, and part of 11: “New Sails for an Old Ship — Building Sails for the Charles W. Morgan“, by Deirdre O’Ryan, from Sea History 147, Summer 2014. This article explains so much so concisely! and has great illustrations too. Ms. O’Ryan has written a dissertation on sail makers of New England, including two women sail makers, and I hope to be able to find and read that someday.

For Question 10: Square Riggers Before the Wind by Wilkins W. Wheatley, a book from 1939 about building model ships, that also explains how real ships worked. All the models in the book are based on the Star of India, which is the museum ship in San Diego that started my fascination with sails! But I found this book all the way across the country, on the used book sale shelf at the Independence Seaport Museum of Philadelphia!

All of these are well written and have much more information than I could include here.

Next time: A wonderfully written description of the work of a sail-maker onboard.

great historical information, it is good to know my AVL WDL could make the 24″ sail cloth if ever necessary!

I read somewhere that it is traditionally basketweave, so now you are good to go!

That was extraordinary! What a compendium of information. Am sending this on……Thank you.

I hope it is useful to someone! Glad you liked it!

The sheer amount of fabric involved with sailing ships is staggering. Sailmaking is another craft that’s been made a niche business due to technology, like blacksmithing. I’m in awe of the sailors who set off across the oceans in those small ships, dependent on the vagaries of the winds.

Like you, I really am in awe of the sailors who ventured out, and also all the shipbuilders who figured everything out too!

Fascinating on all counts – as a lover of textiles and a leisure sailor.

I went out on a sailboat once (fortunately with someone who knew what he was doing) and quickly learned that I cannot think in more than one direction at a time! I can barely sit and duck under the boom (I think that is what it is?) at the same time. It is much better for everyone that I remain a land lubber. But reading all these books about the sailing ships has taught me to understand a little, and appreciate a lot, all the variables and skills that go into sailing, and I am glad about that. 🙂

I never thought of all the planning and work that went into sail making. There’s that song about “red sails in the sunset”, of course. And when I see pictures of sail boats I always think how beautiful there are. I enjoyed reading about them on this page.

I don’t know that song. It has been interesting to me, in reading all these accounts of sailing, how often the men remarked on how beautiful the sails were, even though they were around them for months at a time. They seemed to never take them for granted.

When I weave, I listen to folk music and, for unknown reasons, I have a lot of sea shanties on my Pandora station. They were worksongs, sung to provide rhythm for the raising of the sails and other shipboard tasks. When I read your account, I begin to get a sense of how much those huge sails must’ve weighed–the sailors needed every bit of help to coordinate their efforts to raise them! I will think of you and your research when I listen to my songs!

I will have to search for those songs and give them a listen, to get a better idea of their surroundings.

By the time of Moshulu, they did have winches to haul up the sails, but of course often they didn’t work right. I can’t imagine myself ever having a clue which line went to which sail and understanding which direction it needed to go in!

I have included your blog in INTERESTING BLOGS in FRIDAY FOSSICKING at

https://thatmomentintime-crissouli.blogspot.com/2017/12/friday-fossicking-dec-8th-2017.html

Thank you, Chris

I learn so much from your blogs, thank you.

Thank you, I learn a lot from yours too, and all the fascinating links you provide! 🙂

Glad we inspire each other..

What an interesting post! Oh and I love your blog’s name!

Thanks! I have seen you on Melanie’s blog, Catbird Quilt Studios, and finally had time to look you up! I read three posts last night and am looking forward to reading lots more. Your work with using fabrics beyond quilting cotton looks so interesting. I just got a quilt from a friend who hopes I can repair it — it definitely fits the non-traditional category so I am hoping to pick up some tips from you for using those varied fabrics.

Have you come across any evidence that artists might have used discarded sails for paintings?

No! But what an intriguing idea! Have you come across that anywhere?

I would think that sail cloth would be too coarse to make good painting canvas, but I really don’t know. I have found mention of a town in France called Locronan which was famous for its linen and hemp — that might give you a starting point for more investigation.

Med Islands – Spanish sailors Catalinia types – Berber Moor ocean pilots – sailing ships – 14th Century.

Where and how did they make canvas strong enough for sails to go around the Cape (Africa)?

I got some answers at the Maritime Museum at Soller in Mallorca and sone hints in Valle de Moosa.

But didn’t even know the term ” Technical Fabrics.

The Portuguese came to Goa on one-way tickets.

The Spanish sailors from the Balearic Islands took the ships up and down.

Ocean navigators – Berbers and Moors

Monsoon navigators – Yemen and Konkan

Inbound cargo – slaves

Outbound cargo – fine fabrics and spices.

But the canvas? Who and how and where was it made?

There is a famous company in India, over a 100 years old, called DUCKBACK. They brought American technology in 1920 to India to make waterproof everything. Today they even make the suits that fighter pilots wear.

They have some answers too.

You got me started.

Your notes had a lot of new information for me — and your note taking method looks a lot like mine. 🙂 One simple topic leads in so many directions, right? I sincerely hope I someday get to go to Mallorca to that Maritime Museum, and I will have to look up Valle de Moosa!